| LabGuy's World: Chester Newell,

Tape Recording Genius

NEW! 20150526 Click here to see the prototype Newell tape recorders that were added to the Labguy's World collection in May 2015. I wish to express my thanks to Joyce Newell for bringing these artifacts to light and for sharing them with us here. NEW! 080530 Click here to see the two prototype Newell tape recorders that were added to the Labguy's World collection in May 2008! I wish to express my thanks to Hal Layer for bringing these artifacts to light and for sharing them with us here. ORIGINALY POSTED 050113 Chester Newell had a brilliant solution to high speed tape handling problems! He designed a longitudinal video tape recorder around his method that worked better than any other. His system is still in use today... in computer backup tape cartridges!

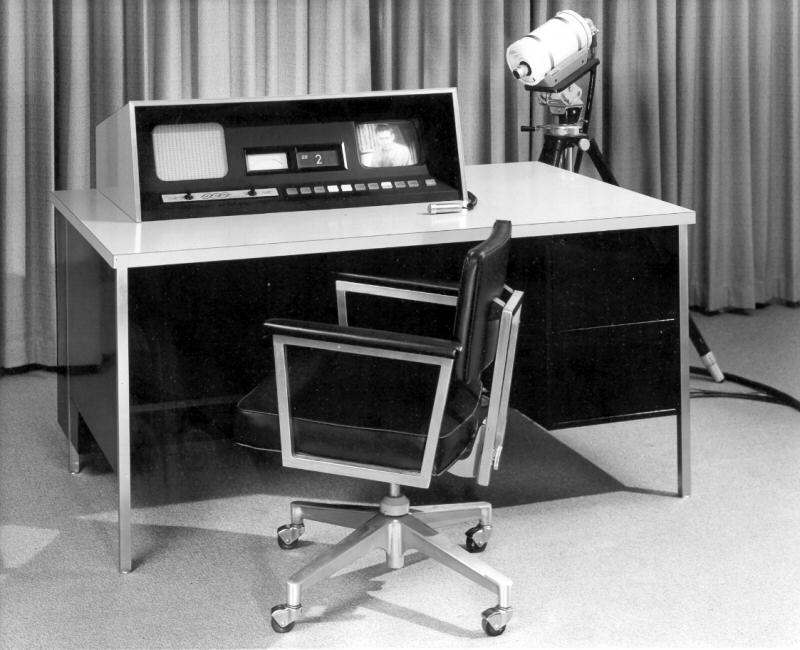

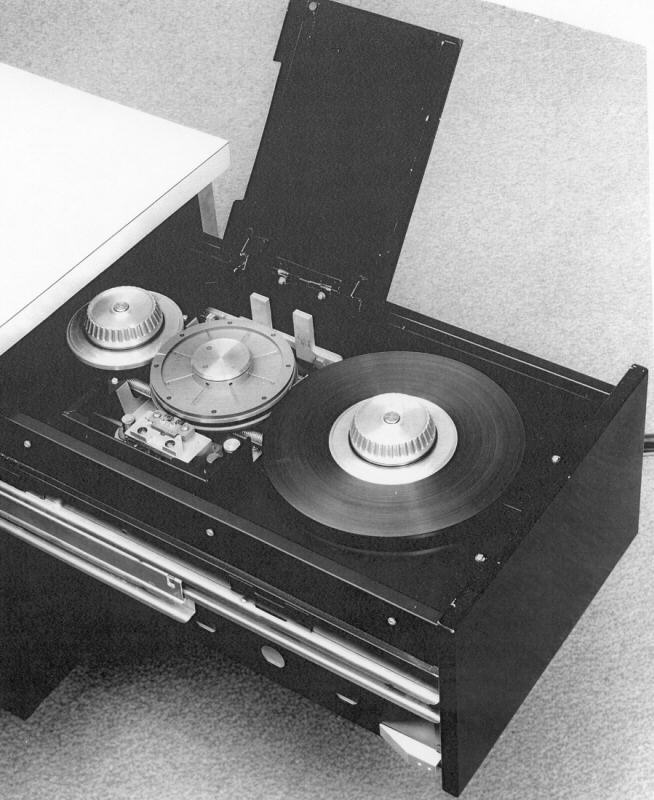

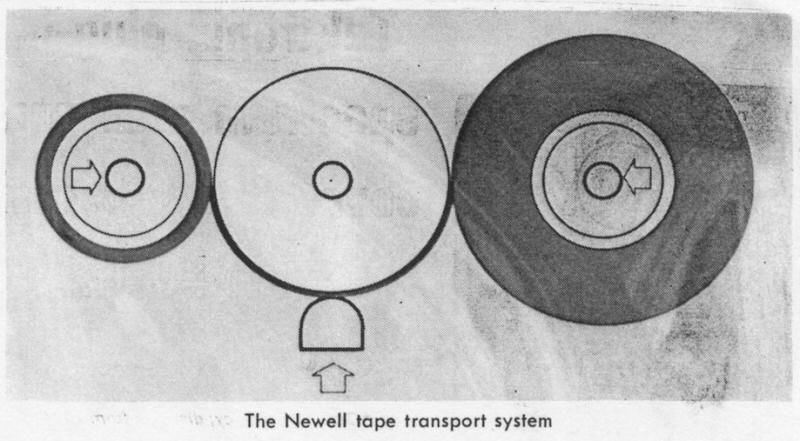

Ches Newell & His Innovative Tape Transport System By Marcel Snijders (C) 2005 In July 1967 Newell Associates of Sunnyvale, California, announced a unique high-speed videotape recorder. This machine with only three basic moving parts ran at tape speeds of up to 1,000 ips (25,4 m/s) with bandwidths of over 10 Mhz. A speed of 4,000 ips (101.6 m/s) with a bandwidth of more than 50 Mhz was said to be possible. As a result of the fact that a single power source was used at the rims of the tape rolls rather than though the tape itself, the tape never existed as an open filament but only in a solid packed condition. Since no power was transmitted through the tape, and the tape existed nowhere in an unsupported condition in the system, rapid acceleration and deceleration could be accomplished without tension effects on the tape.

The philosophy at that time was to develop test/demonstration pieces of

equipment that would allow the technology to be demonstrated in a number

of fields. The objective was to license major companies (IBM,

The Newell-I Principle operated with the two tape packs being directly in contact with a rotating capstan. The packs were wound flange-less hubs and had some kind of a compliant arrangement so that the outer surfaces were always pushed against the capstan. The capstan might be two to four inches in diameter and was mounted directly to a motor shaft. In many ways, this made for a mechanically-simple arrangement.

Floating (vertically compliant) tape heads could rest directly on the tape

as it lay on the capstan rubber surface; or, the tape path arrangement

could lift the tape away from the rubber surface and allow it to pass over

fixed

Performance features of the NI were: 1) Very high acceleration rates. (Typically

1000 in/sec2) 2) High velocities. (Up to several thousand in/sec.) 3) Dense,

stable tape packs since the air had been 'rolled' out from between layers.

Great for long-term storage of important data. Any application that required

rapid searching and data transfers were well suited to this technology.

The main disadvantage for video, as with any longitudinal recorder, is the need for frequent reversal of direction. While this was held to around a hundred milliseconds, it still was (in my opinion) a very annoying glitch every couple of minutes. (It would be a much simpler problem with today's data compression and storage technologies.)

A subsequent development by Chester W. Newell was the Newell-II. This concept

turned the NI technology 'inside-out'. As with the 3M data cartridge, a

metal base plate held pins in fixed locations for the capstan

The following is an interview with Merv Falk, conducted by Marcel Snijders. He worked for Ampex as well as for Newell and was a close friend of Ches. MS - The Idea for the Newell 1 tape transport came to Chester Newell ‘out of the blue’? MF - HE HAD BEEN WORKING AT AMPEX AND HAD MADE SEVERAL DEVELOPMENTS THERE. WHEN HE LEFT AMPEX, IN ABOUT 1962, HE STARTED HIS OWN COMPANY AND BEGAN TO MAKE SOME KIND OF A POWER SUPPLY. IT WAS ABOUT A YEAR LATER THAT HE HAD THE IDEA OF GREATLY SIMPLIFYING TAPE TRANSPORT GEOMETRY AND OF GAINING VERY HIGH PERFORMANCE. SUPPLY AND TAKE-UP REELS NO LONGER NEEDED SEPARATE MOTORS AND VERY HIGH-PERFORMANCE SERVO DRIVES SO THAT THE SPAN OF TAPE CONNECTING THEM WOULD NOT BE OVER-STRESSED. ROTATIONAL ENERGY TO THE TWO TAPE PACKS COULD BE ADDED OR SUBTRACTED VERY RAPIDLY SINCE THE PERIPHERIES WERE TRAVELING AT THE SAME LINEAR VELOCITIES. I NO LONGER HAVE A COPY OF THE ORIGINAL PATENT. ANY PREVIOUS ART WOULD BE CITED THERE. MS - When was the Newell I system for the first time shown/demonstrated to the press or companies as a VTR application? MF - DIFFICULT TO REMEMBER EXACTLY. MY NOTES HAVE LONG-SINCE GONE. I WENT THERE IN 1964 AND IMMEDIATELY BEGAN TO DEVELOP ELECTRONICS FOR PROFESSIONAL AUDIO; HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUDIO; AND THEN HOME ENTERTAINMENT VIDEO. THERE WAS A CLOSED SHOWING FOR POTENTIAL INVESTORS AT A HOTEL IN SFO. BEST GUESS WOULD BE 1966/1967. I REMEMBER THAT WE HAD TAPED A LAWRENCE WELK SHOW -- IN COLOR. IT LOOKED PRETTY GOOD AND EVERYONE WAS IMPRESSED. THERE WAS, HOWEVER, A FRACTION OF A SECOND 'GLITCH' EVERY 2-1/2 MINUTES AS THE TAPE REVERSED DIRECTION AND THE HEAD STEPPED TO THE NEXT TRACK. MS - Did you at Newell develop many VTR prototypes before you had a working machine that could be used to demonstrate this new technology? MF - NO, ONLY THE ONE VTR. WE WERE SPREAD SO THIN BECAUSE WE HAD DEVELOPED DEMO EQUIPMENT IN THE FOLLOWING FIELDS: BROADCAST VIDEO (BEFORE I CAME); BROAD-BAND INSTRUMENTATION; PROFESSIONAL AUDIO; HOME ENTERTAINMENT SINGLE AUDIO PLAYER; HOME ENTERTAINMENT (REELETTE) AUDIO CHANGER; AND THE VTR. A GREAT DEAL OF WORK HAD TO BE DONE ON WAYS TO GET THE HUGE SPIKE AMOUNT OF PEAK ENERGY NEEDED FOR TAPE REVERSAL. OF COURSE, THIS WAS WAY BEFORE IC'S BECAME AVAILABLE FOR REDUCING THE REAL ESTATE NEEDED FOR ALL OF THE ELECTRONICS. INDUSTRIAL DESIGNERS MADE BEAUTIFUL CASES AND HOUSINGS FOR ALL DEMO MACHINES. MS - Have you got any pictures of those VTR prototypes (breadboards most likely)? MF - I WILL HAVE TO CHECK. COULD BE. MARCEL. MS - You told me that the Video application was sub-divided into Broadcast and Home Entertainment. I only know it was tried in some Home VTR's like Arvin's and BASF. Can you remember if it was ever tried in a Broadcast VTR and by which company? MF - I DO NOT BELIEVE THAT THERE WAS EVER A LICENSE PLACED FOR BROADCAST. THE BROADCAST VERSION CONSISTED OF TWO SEPARATE DRIVES WHICH WOULD OPERATE IN RELAY OR 'PING-PONG FASHION. AS DRIVE-A NEARED THE END OF A PASS. DRIVE-B WOULD START, SYNCHRONIZE AND THE VIDEO SWITCH WOULD MAKE THE PROPER SELECTION. MS - Has there to your knowledge been a Japanese company that had a go with this system or took a license on it? MF - YES. WE WORKED VERY CLOSELY WITH OMRON. MS - Your friend Roger Hibbard told me this: "His transport was one of those things that demonstrate very well but never does quite make it in the market place. It was very stable and good when it was running well, but the mechanical adjustments were very critical and not stable over time. It could throw a reel of tape all over the floor in a hurry! " Can you go any deeper into that matter? Perhaps you have some stories or anecdotes about the ups and downs of developing that system.? MF - WHEN I FIND SOME PICTURES FOR YOU, I WILL TRY

TO RECALL SOME INCIDENTS. INDEED, AT 1000 OR 2000 INCHES PER SECOND, A

HUGE AMOUNT OF TAPE COULD GO ALL OVER THE PLACE IF SOMETHING WENT WRONG.

ON THE OTHER HAND, TAPE PACKS, PROPERLY WOUND, WERE EXTREMELY STABLE, BECAUSE

THE AIR WAS SQUEEZED OUT FROM BETWEEN EACH LAYER OF TAPE AS IT WAS WOUND

ONTO THE TAKE-UP ROLL. FLANGES WERE NOT USED ON MOST OF THE DRIVES AND

A TAPE PACK COULD BE THROWN ONTO A CONCRETE FLOOR AND IT WOULD NOT COME

APART. HOWEVER, AT THESE HIGH VELOCITIES, WE DISCOVERED THAT AIR COULD

BECOME TRAPPED BETWEEN THE OUTER TAPE LAYER AND THE REST OF THE PACK. THERE

WAS ONLY A FRACTION OF A

MS - Roger also told me: "It became very expensive by the time it was properly designed and controlled. Millions were invested in that. 3M made a deal with Newel that later was rescinded. Several major companies were interested, but I think all backed out." Can you tell me more about the deal with 3M and the companies that backed out? MF - NEWELL'S PHILOSOPHY WAS TO LICENSE 'GIANTS' OF INDUSTRY TO DO THE NECESSARY DESIGN WORK FOR SPECIFIC PRODUCTS IN WHICH THEY MIGHT BE INTERESTED. THERE PROBABLY WERE SIX, OR SO, LICENSES FOR DIFFERENT APPLICATIONS: IBM FOR DATA (HIGH ACCELERATION RATES, HIGH DATA TRANSFER RATES, RAPID SEARCH); MEMOREX FOR TAPE PRODUCTION; ARVIN HOME VIDEO (YOU SHOULD TALK TO KINGSTON GANSKE AS HE WAS THEIR TECHNICAL GUY); A RECORDING COMPANY (CAN'T THINK OF THEIR NAME) FOR TAPE DUPLICATION; BASF FOR HOME VIDEO; OMRON FOR A BROAD SPECTRUM LICENSE. THERE WERE DISCUSSIONS WITH 3M BUT I DO NOT RECALL HOW IT ENDED. LATER, THERE WERE OTHERS FOR THE N-II. MS - Another piece of information I've got: "The Machine and license were offered to Ampex at least once or twice. Ampex turned it down." Why did Ampex turn it down? They could have used it for their [VR-303 longitudinal VTR] for instance. MF - I DON'T RECALL THAT IT WAS EVER OFFERED TO THEM. THERE WAS CONSIDERABLE FEAR THAT AMPEX WOULD BECOME AWARE OF WHAT WAS GOING ON IN OUR LABORATORIES. MS - Can you tell me more about Chester Newell himself? Some people descibed him as a very creative person but a bit of an 'odd one'. MF- HE CERTAINLY WAS CREATIVE AND CHARMING. HE WAS A REMARKABLE SALESMAN WITH A VERY FAST MIND THAT COULD ANTICIPATE OBJECTIONS AND WAS ALWAYS READY WITH AN ANSWER. HIS TRAINING WAS AS AN ELECTRICAL ENGINEER BUT HIS FORTE EMERGED IN THE FIELD OF MECHANICAL DEVICES. HIS GREATEST SHORTCOMING WAS THAT HE BELIEVED THAT THE N-I TECHNOLOGY WOULD AUTOMATICALLY TURN INTO WORKING PRODUCTS ONCE THE LICENSES HAD BEEN PLACED. THEN, THERE WOULD BE ALL OF THESE CONSTANT STREAMS OF ROYALTY PAYMENTS THAT WOULD FUND CONTINUING RESEARCH. HE WAS A MAN WITH A NEVER-ENDING STREAM OF IDEAS. ENOUGH TO KEEP MANY RESEARCH PROJECTS GOING. WE HAD MANY DISCUSSIONS WHERE MY CONCEPT WAS TO CONCENTRATE ON GETTING ONE THING WORKING WELL; GET THAT TO MARKET AND PROFITABLE. NOW, THE NEXT PRODUCT WOULD BUILD ON THE FIRST -- AND SO-ON. EACH OF THE LICENSEES NEEDED MUCH MORE HAND-HOLDING THAN WE WERE ABLE TO PROVIDE. THEY HAD PRODUCTION PROBLEMS TO SOLVE -- WE HAD OTHER DEMO MACHINES TO BUILD AND OTHER LICENSES TO SELL SO THAT THERE WOULD BE SOME MONEY TO WORK WITH. CHES'S VERY BIG IDEAS ALWAYS REMINDED ME OF AN AESOP FABLE THAT WE READ AS CHILDREN IN SCHOOL. IT WAS ABOUT THE LITTLE BOY WHO REALLY WANTED SOME COOKIES. HOWEVER, THE JAR HAD A VERY NARROW NECK THAT HE JUST BARELY COULD GET HIS HAND THROUGH. IF HE HAD TAKEN ONLY ONE COOKIE, HE WOULD HAVE BEEN SUCCESSFUL BUT THE BOY WANTED A WHOLE HANDFUL AND, AS A RESULT, GOT NONE. MS - Did Newell himself tried to develop a VTR and offer it for sale? I've attached two scanned pages (Newellp1.jpg and Newellp2.jpg) which point in that direction. Any comments on that? MF - NO. NEWELL NEVER DID TRY TO DESIGN A VTR FOR PRODUCTION. THIS RELEASE REFERRED TO THE DEMONSTRATION IN SAN FRANCISCO THAT I MENTIONED EARLIER. ON THE OTHER HAND, THE N-II WAS EXTENSIVELY DESIGNED FOR AUTOMATED PRODUCTION -- AS A COMPETITOR TO THE 3M LINE OF 5-1/4-INCH AND 3-1/2-INCH DATA CARTRIDGES. MS - I've also attached a scanned page of a fixed-head [VTR from Fairchild/Winston]. Were they using the Newell tape transport system as well to your knowledge? MF - I DO REMEMBER THAT WINSTON DRIVE AND DID SEE IT. NO, IT WAS NOT NEWELL TECHNOLOGY. MS - Did you know that BASF together with Blaupunkt developed a miniLVR system using he Newell system that was so small that they've even build it into a Eumig Video camera and making in this way one of the first camcorder prototypes? I've attached some pictures of this miniLVR. MF - YES, WE WORKED CLOSELY WITH BASF. THEIR CONTACT MAN WAS DR. GERHARD ROTTER, NOW LIVING IN LA. THE DEPARTMENT HEAD WAS DR. UHL. TAPE WAS ALWAYS A BIG PROBLEM AND THEY HAD A PRODUCTION FACILITY IN WILSTEAD (SP?). I DID TRAVEL TO LUDWIGSHAVEN SEVERAL TIMES. MS -Both Arvin and BASF mention in press publications that the tape drive system of their longitudinal video recorders is BASED on the Newell system. Were there so many own variations on this tape transport system possible that those companies used the phrase 'based on' in stead of 'working with'? MF- BOTH HAD LICENSES TO DESIGN, MANUFACTURE, AND SELL PRODUCTS. I SUPPOSE THAT SINCE EACH LICENSEE WOULD MAKE THEIR OWN DESIGN, THE WORDS 'BASED ON' WOULD BE APPROPRIATE. WE CERTAINLY DID NOT INSIST THAT THEY USE OUR DESIGNS BECAUSE THEY WERE DONE TO SHOW FEASIBILITY AND NOT OPTOMIZED FOR PRODUCTION. MS -Can you tell me more about Omron and what it did with the Newell system? MF - OMRON INVESTED DIRECTLY IN THE COMPANY. THEY ATTEMPTED SEVERAL DESIGNS -- MAINLY IN AUDIO. NONE WAS EVER TAKEN TO PRODUCTION. MS - Was only the Newell I system used in VTR or also the Newell II? ONLY THE N-I. THE MAIN IDEA OF THE N-II WAS TO DEVELOP A LINE OF DATA CARTRIDGES TO COMPETE WITH 3M, VERBATIM, DEI, ETC. MS - You saw the Winston/Fairchild drive you told me. Can you tell me a bit more about that one? MF - NO, I CAN'T RECALL ANY DETAILS. THE MAIN CONCLUSION AT THAT TIME WAS THAT THE PICTURE WAS VERY POOR AND THAT THE TECHNOLOGY WAS NO THREAT TO US. (END OF INTERVIEW)

Here's the new information I received from Fred Pfost about Chet Newell and his work: My comments and editorial changes to what Fred has given to you - SOURCE: ??? Chester Newell graduated from the University of Alberta with a BScEE. He was one of ten, or so, who was invited to Join the Canadian General Electric, Electronics Training Program in Toronto, Canada. This would have been 1953, I believe. After completing this one year training, he began to work in their Broadcast Engineering Department where he worked on TV studio equipment. CGE was the Canadian representative for AMPEX and during his ETP training period, Ches had gotten to know some AMPEX people. I was on the same ETP program one year later and this is how I got to know Ches. In about 1957, Ches accepted an offer from AMPEX and moved to California. He was excited about the company and convinced me to join, which I did in 1959. Ches always had a million innovative ideas, some of which were great and some of which were goofy -- all were very clever. One of the great problems of the VR-1000 quad-headed

machines was that of timing errors (jitter, flutter, quadrature error,

etc.) that were introduced by mechanical errors and instabilities. Direct

color recording, the ultimate goal, required timing errors to be held to

within a few nano-seconds -- clearly impossible with any mechanical record/playback

system -- without some form of a 'rubber' delay line that could be caused

to stretch and compress in such a way as to undo these delay errors. Ches

had such a scheme and some funding was made available to build some kind

of a demonstrable breadboard. Fred Pfost was a very clever, hands-on kind

of guy who could build some of the strange electro-mechanical devices that

Ches needed. (Remember, this was well before there was such things as an

integrated

About 1962, Charles (Chuck) Coleman had developed a variable delay line Time Base Compensator (TBC) while working for WBBM, a Chicago TV station. It was a brilliant concept using a balanced m-derived delay line with varactors to provide about a microsecond of compensation. This design was purchased by AMPEX and that pretty much terminated Newell's program. Ches then decided to go out on his own, to form a company and to get rich. I guess that this would be in 1962. His first product was a small, compact power supply. Then, the N-I idea hit him and he built some demo 1/4-inch tape movers using series-wound vacuum cleaner motors and Variacs to achieve handling velocities of well over 1,500 inches per second. Needless to say, anyone who saw these tape packs shrinking and expanding, while the motors were screaming, was very impressed. A public corporation was formed and a lot of money raised. Many people did make a lot of money. During this time, licenses were placed with the belief that the giant companies would pour the needed $$$-millions to design and produce the products, each generating a royalty stream. This flow of money was then to be used to development new ideas which would, in turn, be licensed and generate additional royalty streams. At no time did Newell want to be in production. He wanted to retreat to this 'beautiful research lab in Saratoga' and invent things. When these 'giants of industry' didn't follow through with their part of the concept -- that is, to solve all of the thousands of little problems necessary to go from the breadboard designs into production, the whole house of cards started to come down. The audio cassette, developed by Philips and Sony, seemed to end the self-threading audio 'reelettes'. The one area that had some hope of success was the production of a 1,000-ips, multichannel data recorder. This was for military/government satellite data dumps --not for video. I left in 1975 to do other things and didn't return until 1984 so can't add/correct things that Fred has said about that time period. It was my understanding that the main thrust during this period was a telephone answering machine. In 1972 Newell asked Fred Pfost to work for him and develop magnetic recording heads , but Pfost said no. Looking back Fred has regrets that he didn't accept that job, because Chester seemed to have made a lot of money in that period. In 1975 Chester asked Fred again and this time Fred accepted (under the condition that Fred's friend Ed Seaman joined Newell too) and worked for him in a beautiful research lab in Saratoga. Among other things they were working on a small video recorder. In 1981 he lab was closed. [Ches, along with two other investors had purchased

this Saratoga property, the campus and about a thousand acres. It really

did not close. It became the operational lab for developing the N-II. I

was there to head up the engineering program in 1984.]

Interview with Joyce Newell (rough draft - work in progress - by Marcel Snijders) MS: “Your involvement with Ches his work?” JN: Actually, I was not directly involved in Ches’s work during those first stages of development of the VTR. Later, after our children were grown, I did work with him as his office manager, was on the board of directors, etc., so had more first-hand knowledge of what was going on. I understand that your interest lies mainly with the early activities, so I’m not sure how valuable my contribution will be. However, Ches always talked with me about his work and about the problems and challenges that he encountered on a day-to-day basis, so I did have some understanding of what was happening. I’ll need some time to consider how to answer your questions, and perhaps look back in some of the old files and records to refresh my memory. MS: “Ups and downs of the developments”? JN: I’m afraid details have become rather fuzzy after

30+ years, and as far as the technical ups and downs are concerned, I won’t

be of much help-Merv is your best source for those recollections.

From a more personal viewpoint, I can say that Ches’s enthusiasm and optimism

were contagious, so much so that others became caught up in his excitement

and wanted to share in what he was doing. In the beginning he was

working in our garage with only the funding provided by a few personal

friends, while I worked as a school secretary to supplement our income.

One of the young men from our church, who had a keen interest in electronics

but no formal training, became so excited about the project that he insisted

he wanted to come to work for Ches. Ches explained that he had no

money to hire employees, but this fellow just started showing up for work

every day, with his lunch in a brown bag. He was tremendously gifted-seemed

to have a natural instinct for all things mechanical and electronic-and

proved to be so valuable that Ches put him on salary as soon as funds were

available. He was with the company for several years, until he took

a leave of absence to install a telephone system for a mission organization

in Mexico, and ended up staying with the mission, in charge of various

technical projects. Whenever they met over the years, Ches would

kid him about “when are you coming back from that leave of absence.”

(He might have some interesting recollections about the very early days.

MS: “How did the press react?” and “What did Ches think of criticisms of his inventions?” JN: The response to the press conference was overwhelming. The company hired a “clipping service” to collect articles from the press, and I have a whole scrapbook full, put together by the secretaries at Newell Associates from the clippings sent in by the service-many of them repetitive, of course. Ches was surprised but very gratified by the response. As for criticisms, I don’t think he was terribly concerned. He knew there were valid answers, and that given the chance he could satisfy the critics. MS: “What happened with Arvin?” JN: Unfortunately I don’t have a very clear idea of what happened with Arvin, nor does Merv. The Newell Industries year-end report for 1969 mentions “the CVR Labs at Grass Valley, California, where the home video recorder is being developed under license from Newell.” Merv thinks that King Ganske was in charge for a while, and then later Arvin sent out some “young hot-shot” to run things, which didn’t work. He thinks they concluded that the cost to pursue it into production would be too large, so they eventually dropped it. Merv also recalls the following anecdote about Arvin’s president, Stonecipher (who had been the champion for the project): “Stonecipher got a fish bone caught in his gut and had to go to the Mayo Clinic for surgery. They botched the whole thing, leaving sponges and I forget what-all inside him. I think that it pretty much ended his career with Arvin.” MS: “What went wrong with the further development of the Newell Home VTR” JN: Basically it was a case of running out of money,

caused by a sequence of events that had a sort of “domino effect.”

Some of these were events over which the company had no control whatsoever.

There were others which, in hindsight, could perhaps have been avoided.

His memo explains the basic facts, but perhaps it might help if I add a

bit of background as to the general attitude that persisted throughout

the financial community. In simple terms, it was that an “inventor”

may be a creative genius, but he is usually an impractical, “wild-eyed”

dreamer, who can never be a businessman; instead, his business and financial

affairs must be managed by those with proven management and financial skills.

Ches did not (for obvious reasons!) subscribe to that opinion, but he was

a realist-he knew from the outset that this was the way things would be,

so he fully supported the concept of finding an experienced president to

head up the hardware company. (In fact this was fine with him, because

his goal was to stay in research.)

MS:”Did Ches make any trips to Japan to talk about his invention with companies over there?” JN: the only trip I know of during those years was in September 1968. Ches went over with his patent attorney and a business consultant who was very familiar with Japanese business practices. They spent about a week in Tokyo meeting with several companies, but I’m sorry I can’t recall which ones-Matsushita comes to mind, but I’m not at all certain of that. I believe also there were meetings with the Japanese patent office, in order to pave the way for filing Newell patents in Japan. After the first five or six days, I flew over and joined Ches, and we spent a couple more days in Tokyo, then went on to Osaka for meetings with another company. When all the business was finished, Ches and I spent about another week doing the tourist routine. I’m afraid this isn’t very helpful to you in terms of the companies that were involved, but at least it does pinpoint the time of the trip, and you’ll notice it was several months after the official demonstration in May of 1968. MS: “Has Ches been working on a VTR before he started his own company?” JN: I’ve come across an early memo prepared by Ches

summarizing some of his work history. Referring to his joining Ampex,

the memo states:

JN: Well, at last I have time to “comment on

the comments,” that is, those you sent me from people who worked with Ches

You’ll notice I’m mostly responding to those comments which might be considered

somewhat negative. Naturally, I fully agree with all the positive

ones!! I realize, though, that Ches was by no means perfect, and

that in many ways he did fit the profile of the “Pioneering Personality”

which I think Merv sent to you, namely: unique perception; courage of one’s

convictions; perseverance and persistence; confidence in one’s ability

to succeed. I think Ches had all those qualities, and the extent

to which the negative side of those same qualities was seen probably varied

with the beholder. He also had the ability to infect other people

with his enthusiasm, which I suppose is what made him able to “sell refrigerators

to Eskimos,” as someone (Merv?) said. He did often work alone, but

was never what I would call socially isolated. He loved working with

other engineers, and most of them seemed to enjoy working with him, although

there were cases where they locked horns. Ches himself felt that

he tended to polarize people-either they were intensely loyal and supportive,

or they didn’t like him. Fortunately I think the former were in the

majority.

MS: ? “Ches decided to go out on his own, to form a company and to get rich.” JN: I had to chuckle a bit over this comment, but I

think it deserves a reply. Ches’s main goal in life was never just

to “get rich,” although he certainly anticipated (and even hoped) that

this might very well happen! But his motivation was much more complex

than that. To understand it, one needs to realize that he absolutely

loved being an engineer-he was an engineer to his very core. He loved

coming up with an idea, working out the design for it, putting it together,

and seeing it work-that was intensely satisfying to him. He had no

patience with people who would automatically say that an idea couldn’t

work, before they took the time or trouble to analyze it and find out.

I think Ches would have said “being an engineer isn’t just what I do, it’s

who I am.” (My son said this to me recently about himself as a doctor,

and it’s exactly the way Ches felt.)

MS: ? “Ches always had a million innovative ideas, some of which were great and some of which were goofy-all were very clever.” JN: I suppose the opinion that any particular idea

was “goofy” would depend upon the individual making the judgement.

Ches had the kind of mind that was always exploring possibilities, and

often a train of thought that started out with an apparently “goofy” idea

would lead to something workable and valuable. I recall that in the

early days of the Newell I technology, a Ph.D. mathematician analyzed the

“Newell Principle” and concluded it could not possibly work-while at the

same time it was being demonstrated in working prototypes!

JN: This comment was illustrated by the story about using batteries for power in the lab, to which I believe Merv has already responded. (It may have happened at some point for some specific reason, but doesn’t sound like the sort of thing Ches would do as a sort of fixed procedure.) As for being a “lousy product developer,” this statement ignores the very impressive products that were developed. (You already have information on these). I recall that Ches always made a distinction between “product development” and “product engineering,” and I don’t know whether everyone recognizes the same definitions for the same terminology, or exactly what this person was referring to in his statement. I do know that what Ches most liked to do was to take a new idea from the conceptual stage, through initial design, through prototype, and on to a working model, and he did that very well. Beyond that stage he felt that another set of engineering skills was needed, and he tried to bring in people with that sort of experience to carry the product forward to manufacture, although of course there are always overlapping contributions from both areas. MS ? “Newell’s philosophy was to license ‘giants’ of industry to do the necessary design work for specific products in which they might be interested.” MS ? “Each of the licensees needed much more hand-holding than we were able to provide.” JN: These statements are fairly accurate. Ches

saw tremendous potential for the Newell I technology in many applications,

and believed it would be foolish for one “newcomer” in the industry to

try to develop them all. With technology advancing so rapidly in

so many fields, he felt that a new, relatively small company could never

hope to expand quickly enough to cover all these application areas.

His hope was that by licensing other companies with expertise in those

different areas, the technology could cover the broadest possible spectrum

in the shortest possible time.

MS ? “Later there were others for the N-II” -- (that is, other licensees). JN: This statement is not completely accurate. Because of his disappointment with the Newell I licensing program, Ches actually determined on a different approach with the Newell II-specifically, to form a manufacturing company which would be exclusively licensed to produce and market the new data cartridge. The story of that company (Cartrex Corporation), however, is far afield from the history of video tape recording! (He did license Genisco Technology for military applications of the Newell II technology, and several of those went into production and were used in military equipment-even generated a fairly substantial royalty stream for a while. However, when the royalties grew large enough to be uncomfortable, Genisco decided just to stop paying! In that situation, the only recourse is to do an exhaustive audit and bring legal pressure to bear, and we just didn’t have the muscle to fight them.) MS: ? His big failing was that he couldn’t bring himself to take the best deal possible; he kept trying for the best possible deal. JN: I believe this was Merv’s comment, and I think it applies more to the Newell II project, with which Merv was also closely involved. As discussed above, during Newell I most of the focus was on licensing. Companies in the various fields of expertise were licensed for a prescribed license fee, and I don’t believe that holding out for “the best deal possible” really entered into the situation at that time. I know that sometimes during Newell II, however, there were differing opinions regarding a particular “deal,” and it’s very difficult to make a judgment as to which opinion was right. Obviously, each person had good reason for holding to his own point of view. In Ches’s case, he had to consider not only his own inclinations, his own technical and business instincts and the technical advice of his engineering staff, but also the opinions of his board of directors and the rights of his investors. The first company, Newell Industries, had gone public with its stock, so the earliest investors were able to realize tremendous returns on their original investments. This was not the case in the second company, Newell Research. It was privately held, and the investors were looking to Ches to protect their investments and bring them to fruition. Several of his leading investors and board members had very unrealistic ideas as to what we should “hold out for” in any negotiations, and Ches often spent hours on the phone with them explaining what he thought we might-or might not-be able to achieve. So it was a balancing act, trying to negotiate a deal that would be realistic, and yet one that wouldn’t give away so much that we’d regret it down the line. He was very good at spotting pitfalls in a contract-little items that the other side would slip into a document, hoping that he would think it was something innocuous, but when he would pin them down as to what it really meant, it would turn out to be something that would have led to big trouble later on. Ches always felt that a good deal meant one that was good for both sides, and that was what he tried to accomplish. MS: ?“Ches’s eternal optimism would block the details of reality.” JN: It’s certainly true that he was an eternal optimist, and this probably led him to venture more than he would have otherwise. By and large, though, I never felt that it was having a negative effect-quite the contrary. He simply refused to get bogged down in worrying about all the possible problems that could arise. He just assumed that when they arose they’d be dealt with and there would be a way to solve them. But for an entrepreneur, I guess if one has to choose between being too optimistic or too pessimistic, you’d pretty much have to go for the optimism. MS: ? “Ches was an extremely bright engineer, with a fertile mind, but was not in my opinion sufficiently pragmatic, and couldn’t be wrong.” JN: I think there are several ways of looking at this,

because Ches was extremely pragmatic in some ways, and perhaps not in others.

For instance: In the process of working out a development contract, for

which Ches would be negotiating funding (either with investors or with

some other company), the engineers would lay out their schedules and their

budgets, allowing lots of nice, comfortable time for things to go wrong,

etc. Ches would look at it and realize that the funding source would

never agree to that schedule and that budget-it was too long, and too “rich.”

So he’d tell the engineers they’d have to do it in a shorter time and for

less money, and there’d be howls of protest. But eventually they’d

whittle it down, and Ches would get his funding. Okay-some would

say his expectations for the project to be accomplished within those parameters

were impractical and unrealistic. On the other hand, he knew it was

the only way he would have been able to get the funding. And he also

knew that if they got three-quarters of the way through the project and

needed more time, or more money, but were showing good progress-he’d get

what he needed. And he was usually right. So, was he practical

or impractical?

All Material Contributed by: Marcel Snijder 05.01.13 (C) 2005 Marcel Snijders & Labguy's World [HOME].........[VTR PEOPLE] Created: January 13, 2005 Last updated: June 08, 2008 |